Driving a circular economy in seafood supply chains

It’s estimated that around 35% of global seafood production is lost before reaching consumers (FAO 2020.)

Discarding skin, shell and other by-products during processing creates waste which is both environmentally damaging and economically inefficient.

But the Iceland Ocean Cluster (IOC) - a community of over 70 companies and entrepreneurs working within aquaculture, fish sales, marine technology, software, design, biotechnology, cosmetics, and other sectors - believes that working within a ‘circular economy’ can go a long way to closing that loop between production and consumption.

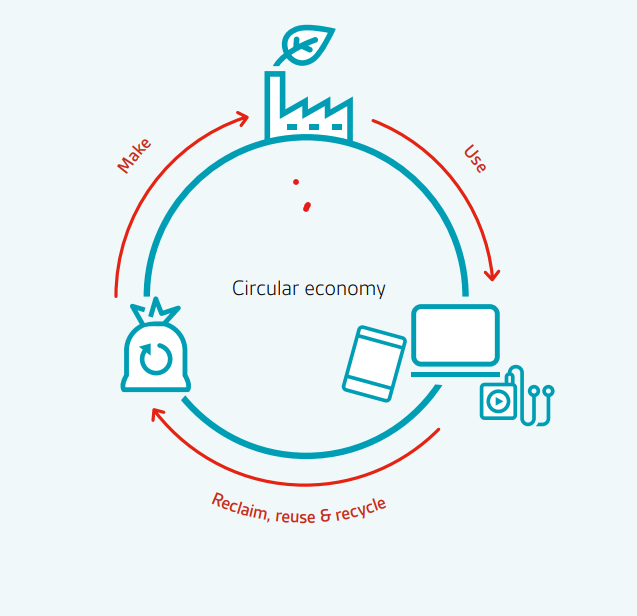

Our traditional approach to production and consumption followed a wasteful linear economy of ‘take, make, use and dispose’; whereas the circular economy is about:

re-thinking how resources are managed to create financial, environmental and social benefits both in the long- and short-term.

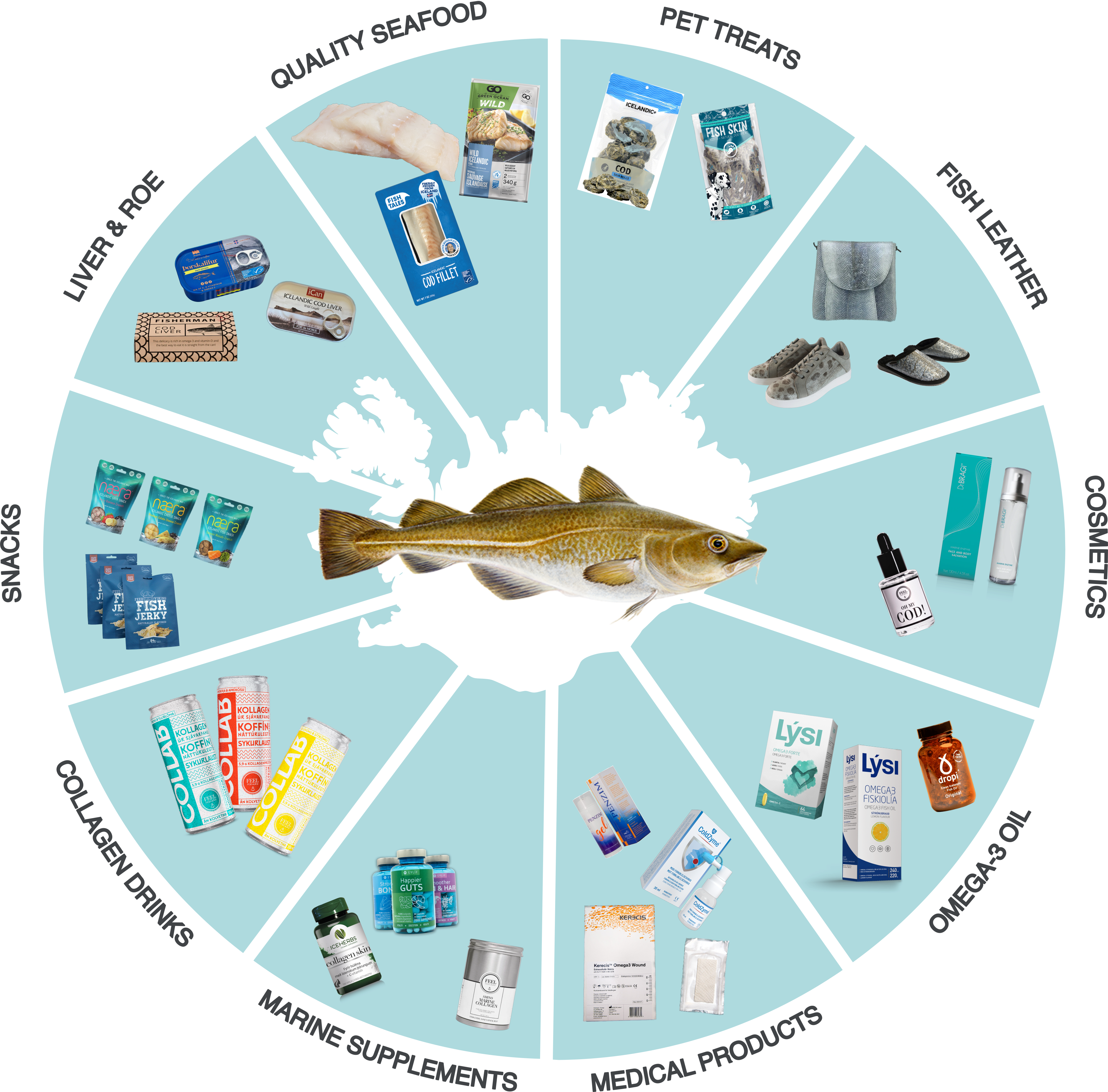

The IOC’s 100 % Fish Project operates with a circular economy framework in mind and encourages companies within the seafood industry to use every part of a harvested fish, arguing that repurposing the more traditionally discarded fish waste can reduce waste management costs while also opening up new income streams from new products.

The IOC – a bridge building cluster

Based in Reykjavik, the IOC operates as a cluster business, spanning all sectors including fish sales, marine technology, biotechnology and cosmetics. It bridges the gap between traditional sectors such as fishing and processing, with academic institutions,, and startup companies/entrepreneurs.

Alexandra Leeper, Managing Director of the IOC, said: “There’s a natural divide in the languages these groups speak, and our focus is on closing that gap.

“Previously, large industry-focused companies operated in isolation, neglecting to exchange ideas on solutions to shared challenges, hindering collaboration and innovation.

“This lack of cooperation stifled progress not only in fisheries but also in the broader blue economy. The IOC emerged as a solution, providing a platform for open dialogue.”

The 100% Fish Project started early in the cluster’s formation to address declining catch volumes due to quota restrictions.

It aims to maximise value from reduced catches by using all materials to create co-products, transforming the seafood industry towards zero waste.

In Iceland, the seafood industry has now achieved an impressive 80% utilisation of white fish.

A single Atlantic cod fish, valued at c. $12 for its fillets, now has the potential to generate over $5,000 in value (IOC, 2022). This is possible due to innovative and advanced processing techniques, which allow every part of the cod to be transformed into high-value co-products.

The circular economy in action

Kerecis is developing a biomedical skin graft from cod skin. Its website includes several peer reviewed papers on the science behind its products.

Codland use biotechnical solutions to develop mineral supplements e.g. calcium from fish bones, fish oil, fish meal and marine collagen.

FEEL Iceland extracts fish skin collagen for human skin and hair etc. and most recently worked with Ölgerðin to produce Collab, a collagen-rich energy drink.

Primex harnesses co-products by extracting pure chitosan (from North Atlantic cold-water shrimp shells) to offer an alternative to synthetic chemicals used in several industries including cosmetics and biomedical.

Nordic Fish Leather offers natural and dyed Atlantic salmon and spotted wolffish leather used in a range of high-end fashion products, including shoes, belts, handbags and accessories.

Fish leather is globally prized in fashion for its softness, flexibility and durability. In the UK, its use has been limited to small-scale fashion projects, but signs of growth are seen in companies like Moray Luke and Felsie. With brands like Nike, Prada and Dior starting to incorporate fish leather, it’s an industry trend to look out for.

Entire supply chain benefits

"While the rising value from innovative applications is significant, it is essential to ensure it benefits the entire supply chain, including fishermen,” Alexandra Leeper added.

“Marine Collagen, an Icelandic vertically integrated company, serves as an example. With ownership of vessels, processing facilities and the marine collagen production site, it ensures that profits are reinvested into fishermen's operations and facilities."

Drawing from Iceland's experiences, the IOC has developed a model for international implementation.

Alexandra Leeper explained: “We always begin by thoroughly understanding and mapping the existing landscape: identifying species, available volumes, and associated infrastructure like logistics and cold storage.”

“We assess waste streams and collaborate with research partners to explore the functional characteristics of materials.

“Then, we evaluate market interest, product possibilities, pricing, and viability for a business plan.”

A worldwide network of companies now operates through the Ocean Cluster Network, partnering a variety of stakeholders, such as governmental bodies and global technological leaders in food processing such as Marel.

Alexandra has already worked with companies within the UK.

Opportunities ahead

In the UK, utilisation of seafood by-products has more traditionally involved lower-value applications like animal feed and fish meal, with shells repurposed for road and garden aggregates. However, research increasingly indicates that with improved processing techniques, higher-value compounds like proteins, vitamins, collagen and chitosan can be extracted from fish by-products.

Stuart McLanaghan, Seafish’s Head of Responsible Sourcing, added:

"Driving sustainable resource management across the seafood sector will support businesses to build supply chains which are more resilient to external shocks and disruption; unlock exciting new product revenue streams; deliver environmental sustainability credentials; build brand following; and minimise traditional bottom-line waste management costs. With almost 360 seafood processing sites across the UK, there are exciting business opportunities ahead from applying the principles of a circular economy across seafood supply chains.”

Shell-eberating sustainability in the UK

Cuantec, an established company based in Scotland, is extracting chitin, a by-product from Nephrops and a highly valued and profitable commercial compound.

Rupert Maitland-Titterton , CuanTec's CEO, explained "We start with a whole langoustine. The protein is separated from the shell, containing various biological components which is purified, leaving chitin, a natural polymer. This can be refined into chitosan which is a valuable material for many applications including cosmetics, agriculture, water purification, food and medicine. Essentially, we turn a by-product stream into a valuable product for use in multiple sectors."

Mr Maitland-Titterton is keen to source raw materials from UK-based processing companies which in turn source Nephrops landed by UK vessels. With the rapid growth of the chitosan market and 28,191 tonnes of Nephrops landed into UK ports by UK vessels in 2022, a significant opportunity exists.

"Processors must offer the same traceability for the shell as they do for the protein,” he added.

“Then it will be possible to target high-value sectors. By diverting by-products from landfills and energy-from-waste, processing companies can also avoid paying associated waste management costs, while becoming environmentally friendlier.”

Having finished their lab research, CuanTec have recently opened a new factory in Glenrothes, Fife, producing pure chitosan for the biomedical and pharmaceutical industries.

Additional advancements in the industry include Pennosan Ltd, a Welsh-based company producing and distributing eco-friendlier water purification products. Their formulations contain a chitosan liquid derived from discarded mixed crustacean shells sourced within the UK.

Similarly, Andrew Brown, Director Sustainability and Public Affairs at MacDuff Shellfish Ltd, Europe's leading processor of wild shellfish located in Scotland, said: “We are involved in a number of research projects looking to utilise chitin from Nephrops carapaces.”

One of their foremost initiatives involves working with soil researchers at the Hutton Institute and Dundee University to develop chitin from wet waste into soil treatment, to combat a parasitic nematode, or potato worm, a pest of potato crops in Scotland.

UK Fish Waste

In the UK, many potential uses for fish-by-products remain in research and development.

However, in 2019, Pelagia, a prominent producer of pelagic fish products and a leading innovator, expanded their Bressay plant in the Shetland Isles. They obtained a license to utilise by-products from Scottish salmon farms to produce the UK's first liquid fish hydrolysate, Sea 2 Soil, a fully approved organic soil improver.

Additionally, Mark Hamilton, CEO of Surfteic, a Scottish startup who has connected with the IOC, claims to have efficiently transformed fish oil waste from Scottish salmon farms into sustainable biosurfactants during feasibility research funded by IBioIC and Sustainable Aquaculture Innovation Centre (SAIC). If successfully commercialised, this could offer an alternative to the fossil-fuel and palm oil-based surfactants found in detergents.

Mark added: “At Surfteic, we embrace the principles of the circular economy. We repurpose aquaculture industry waste into high-value products, closing the resource loop and reducing waste. The next stage of the journey for Surfteic is to secure funding and partners for the first stage scale-up in a bio- renewable centre to start producing larger volumes.”

The future…

The IOC 100% Fish programme promotes a clear message: it is possible to achieve near zero waste and reduce greenhouse gas emissions through new innovative processing techniques. It is not only economically viable, but also economically rewarding for the supply chain. Moving forward, work between UK-based researchers, start-ups and technology providers would be beneficial in facilitating knowledge sharing and idea exchange. By implementing technological, operational and behaviour changes the sector can begin to reduce carbon emissions and promote sustainable development pathways with the goal to achieve Net Zero by 2050.

References

The British Standard Institute (2017). Executive Briefing: BS 8001 -a Guide. [online] Available at: bs8001_executive_briefing.pdf (bsigroup.com)

FAO. 2020. The State of World Fisheries and Aquaculture 2020. Sustainability in action. Rome. https://doi.org/10.4060/ca9229en

Food and Agriculture Organisation of the United Nations (FAO). (2022). The State of World Fisheries and Aquaculture 2022,. [online] Available at: https://aquaculture.ec.europa.eu/knowledge-base/reports/state-world-fisheries-and-aquaculture-2022

Food and Agriculture Organisation of the United Nations (FAO). (2024). Climate Change: La pérdida y el desperdicio de alimentos en las cadenas de valor del pescado. [online] Available at: https://www.fao.org/flw-in-fish-value-chains/en/

Íslenski sjávarklasinn (2024). 100% Fish. [online] Available at: https://sjavarklasinn.is/en/iceland-ocean-cluster/100-fish/.

Seafish (2023a), Processing Enquiry Tool, Public.tableau.com. Available at: https://public.tableau.com/app/profile/seafish/viz/FleetEnquiryTool/1Overview (Accessed: 09 February 2024).

Seafish (2023b), Fleet Enquiry Tool, Public.tableau.com. Available at: https://public.tableau.com/app/profile/seafish/viz/FleetEnquiryTool/1Overview (Accessed: 09 February 2024).